The Wires

Jacob Holmes-Brown

short fiction | 23/04/2020

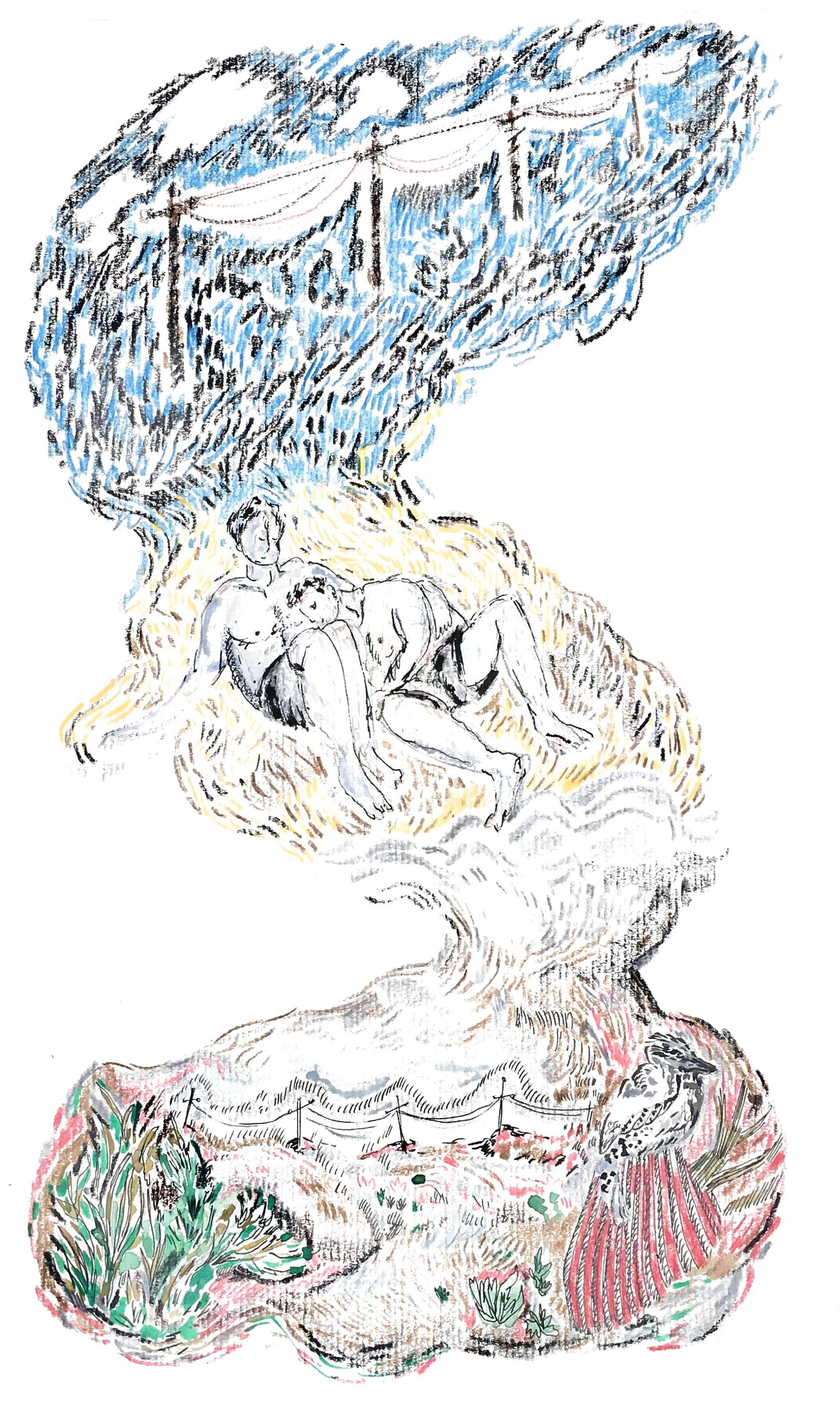

illustration by Benedict Leader. two men lie in a field. above them are telegraph poles. to their right, two people sit on a park bench in lush greenery.

I’d heard that in the desert, at night, you can hear the telephone lines speaking.

On the outskirts of Geraldton I stomped out to where the road runs into red dirt and that grey-green West Australian scrub. An old Aboriginal man spoke up from the bench at the bus stop, interrupting my staring into that vast space, “The fellas talking to each other or just spinning a yarn for themselves?” His pointing finger traced the swooping wires between roughly hewn poles running a straight line out into the darkness. “Ya hear it?” Under the faint ache of the desert wind;

It bends and moans like a tuning orchestra, a clattering factory assembly line; chittering insects and birdsong all at once. But I don’t know what damn language that is.

There were only cicadas and the beat of his beer bottle tapping a rhythm on the metal bench. I shrugged. I thought of returning to the family dinner table. Mum’s cutting “where’d you run off to?” and Dad’s equally quick leap to my defence. They’d circle back to my leaving Sydney, my imminent departure for the UK… and questions about Lucas. “Didn’t he want to come with you?”

* * *

It comes back to me now, staring into another vastness: the towering folds and grooves of the sheets where the man I barely know has rolled out of bed. Speedo guy- Mark (his picture was waist down, green speedos) is in the shower. I didn’t offer him a shower.

Before me is a desert of cotton sheets and only the dumb commentary in my head for company. I twisted around to crack open the window, between my blood still pounding from exertion and the central heating, I was sweating. Welsh winter air brushed down my neck and settled its cold weight across the right side of my chest. I can’t put my arm around that.

“That project you mentioned on the app, what’s the focus of it?”

I hadn’t heard the shower stop.

“Environmental adaptations and public space.” My voice sounded disembodied to me, falsely light. “Nice, that’s cool,” the same strain from him too, weird to hear out of the mouth a guy almost a decade older than me. “So, what’s the most exciting idea we can implement?” Still damp he slipped his jocks on, the fabric clinging to the circumcised shape of him. His probing to see if there was more to what we’d just done, the small kindness in taking an interest, made me want to punch him.

We were still chatting, somehow now on Aussie cinema, as he stood there in the drizzle. His “It was nice to meet someone intelligent…” hung between us like a hook I didn’t want to take. “If I see you on the app I’ll hit you up,” I said, dashing whatever he was nurturing. His manner had torn something inside me loose.

* * *

“It’ll be a really good opportunity for you,” Lucas almost did a good job at hiding the hurt. “I’m stressed about it but-” I know I paused before I said the next part, I know I turned it over and examined to see if it’d work, “-there’s nothing for me here.”

I felt it before I saw it on his face, before the faux-casual tone had even vibrated its way to his ear drums. I had sliced something free. Why can’t I be honest?

“Career wise, I mean. If I want to do this at the federal level and be involved in the policymaking I’ve got to get experience-” I stopped the tumble, there was no point trying to save the last nine months.

Lucas nodded, “Makes sense why you didn’t want me to move in.”

I wanted to run my hands through his tightly curled black hair and pull him into a fierce hug that’d tell him, “We were going really well but it couldn’t go on forever.”

“I only just decided this.”

He shrugged my answer away, struggling to find the response between his facade and his need.

“Do you want to stay tonight?” I knew it was unfair, he’d accept, then I’d spend the night second guessing my every word and movement, all too aware of what was going unspoken. I didn’t want to let him go but he was so much more sensitive than me.

This is my responsibility.

The drilling laugh of a kookaburra woke me up. The light of a glary Summer day already breaking between the blinds.

I planned to make Lucas shakshuka for breakfast, but it was too early yet. I had bought good Orange Juice too. The ceremony was unplanned, but the reckless little parts of me trying to find ways to express my love were louder than the big cautious ones.

I slipped my arm beneath his head and he rolled into me. The scruffiness of his beard on my chest and his face bowed down so that his full lips almost met my skin with a kiss. My skin, with its only-the-start-of-Summer tan, looked all the more pale next to his. If I stayed, through Christmas, by the time we hit my birthday in Feb, we’d both have tan lines, mine stark, his subtle. I was creating a damn memorial before it was even over.

I imagined my hand walking down the thicker clump of hair between his pecs and through the hair across his stomach, running my fingers inside the waistband of his boxers. Last night I’d done the same as he kissed me, his kisses slightly too fast to match my pace.

Lucas was ten months older but there, delicate and unselfconscious and comfortably asleep, he looked like a child. I feel like a child right now, with this- that word from the Lord-of-the-Rings book he made me read- Leavetaking?

* * *

Speedo guy has vanished around the corner, probably to find the car he parked a “discreet” distance away.

Some part of me wants to run after him and invite him back for a cup of tea and a chat… about anything. The little things he’d told me resurface: has a young daughter living with her mum; not originally from Cardiff but loves living here; a previous job as events manager for an Equestrian company. But he’d take this as investment when I only mean it as a way of forgetting.

I struck out to the left, opposite from the way that Speed- Mark walked.

My keys chimed with every step, loose in the fabric of my track pants. My gaze grazed the windows of passing houses with the hopes of seeing into them. Lit up goldfish bowls of human lives. I wanted to see it, some refutation of my own loneliness. I’m not as lonely as some though. One golden tableau of a dad holding a toddler holding a dog teddy, the man talking to someone in another room as his son taunts their Labrador with his toy.

I sensed the pole the instant before I hit it, as if the space between us compressed and brushed against the hairs on my cheek. That’ll bruise. And I looked up:

The wires at the top splayed out to the row of houses beside me.

It was so different from Australia, here there were none of the telephone poles ubiquitous of every older Australian suburb… and country area… and all the way out across the wilderness. Here there were none of the those Eastern Orthodox cross shaped wooden totems with their three top wires and four below. Did it matter?

All these houses were connected to this one pole, a single wire to each.

If the wires really could talk then in Australia you could talk to anyone, here only to the people in your little row? And if you didn’t know anybody in your row? What if they were 17,000km away? I stood still, letting the misty rain seep into my jumper and track pants and hair, shoved my hands into my pockets and listened. A bloody car driving too fast through a puddle.

I imagined lilting Welsh in banal conversation about Love Island on catchup and whether to order Papa John’s or Domino’s. That’s just noise.

A single wire swung out and away from the houses and, without thinking, I followed.

I’d been standing on the edge, not realising how close I was until that push. Perhaps this was a bit of a desert, me locked away in self-isolation and the road stretching either way with its uneven surface, puddles and bordered by wet footpath.

I followed beneath it across the bitumen and then back. Then across a junction and around the corner where- the wire ran out. I stood at the end of a short road leading into Bute Park. There were no telephone poles in Bute Park, this was as far as it went.

* * *

His voice was higher than I remembered from the party, but spoke to me of care and an easygoing peace at his place in the world. He watched me over his menu as I pretended to study mine. As if I wasn’t just having the same smashed avo on sourdough.

“It’s a nice place. I never get to come to the inner-west but there’s some good cafes here.”

“Almost as civilised as north of the bridge?” I teased.

“That’s not what I meant-” he dropped it as soon as he clocked that I was teasing and threw it back at me, “You’re not even from Sydney so why are you weighing in on the north/south issue?”

“Makes me an independent adjudicator,” I countered. I was taller than Lucas, enough that I could see the way his eyes kept straying to my mouth as I spoke. I loved that it continued all through breakfast. His softness welcomed my vulnerabilities.

“Why are you laughing?” he asked. His directness sent me flailing, “I’m just smiling.” It sounded so fucking lame. How do you explain being momentarily free of arbitrating on future plans? I tore my gaze from his and threw myself into the shape of his biceps, the black hair on his forearms and his one hand, scratching at the callouses on the other.

“I guess an impromptu date on a Friday morning makes work a bit easier, ay?” There was a question there, he wasn’t sure if this follow up date to some chance meeting was going to work. I gave over to my desire to buy into that fluttering feeling, “It’s nice to be here with you. I didn’t know if you’d say yes.” I don’t think I’ve ever been so honest in my life.

* * *

“Hey,” my voice fell flat in the damp air and slipped to the concrete reaching no-one’s ears but my own. To my own it sounded like a slap.

I stepped back into the shadow of the tree, shielding from the street lights and potential passing cars and the people in all the houses around me, hundreds in this tiny radius. And I’m here trying to talk to a lamp post.

Shame burned in me, shame at wanting to fix something I’d ruined. I needed to try.

“Lucas, mate,” the rational part of my brain tried to choke the words, probably keeping me from a mental asylum, “you were more invested than me and that wasn’t fair. I wasn’t ready to settle down and I couldn’t ask you to leave Sydney on the chance…”

I looked around to see if anyone could see me a complete dickhead talking to himself - but I wasn’t really looking, I was imagining the response: “You didn’t ask me what I thought.”

What did that sound like over the wires?

The bow over a cello string, the unceasing slow drip of water, the screech of dial-up internet.

* * *

We drove an hour north of mine to the Northern Beaches for a swim.

Just shy of 30 degrees and the late afternoon sun turning the water into emerald blue. A green that you could only appreciate if you were in it.

He duck-dived under the creamy tops of the ragged waves breaking around us - the surf was crap. I jerked my hand away as I felt something touch it. I always had a tiny corner of my mind reserved for shark attacks, but it was Lucas. He floated next to me as a wave crashed over us.

I brushed the stinging salt water out of my eyes. He was laughing, he enjoyed hurling his body into the fray. I was wary of rips.

The sight of the sun curling around his brown skin, polished into glowing warmth, sunk into me. I wanted to wrap him up in my towel.

illustration by Benedict Leader. two men lie in a field. above them are telegraph lines; below them, a Kookaburra sits on a tree stump.

“Let’s grab fish and chips before we go home.” It wasn’t a question, he was more direct these days with what he wanted. In the casualness of his voice, “home” felt like the place that we both were.

* * *

My brain kicking me while I’m down.

I pushed back the urge to punch that stupid wooden post, hoping the vibration shook those wires enough that words, or at least real sounds, would fall free. But here wasn’t there and my messages couldn’t travel that distance.

Could the people across the road hear me even as some weird metallic hum- projected into their living rooms? I was here not there. What was I even doing here?

What if I were there?

What if this single post - if I grew it in my mind? Pinned two crossbars to the upper reaches and sprouting it with rows of corded metal cable? I pushed the nighttime soundscape of Cardiff from my hearing and conjured the cicadas. I planted my feet, imagining the sand beneath them and the last of the day’s heat rising up and the sun setting behind, painting my back with light. “Mate,” I didn’t care how loud my voice sounded now, “this sucks.”

I want to pack it all in. “I want to pack it all in.”

I want to go home. “I want to come home.”

But - “But I don’t expect you to take me back or us to continue as it was before or anything…”

Say you’re sorry.

The sand eases around my feet and I shift my weight forward. I lift my voice to vibrate to the wires, all seven of them, reaching all the way from Western Australia to Sydney, across the bridge and northward to him. And he’s standing in the sand too, but on a beach, and he can hear my voice in the wind. It’s brushing down his neck, just behind his ears where I loved kissing him. I hope it gives him the same goosebumps.

I didn’t want this all to sound like some pathetic “sorry”.

I stood in silence for the longest time.

Chalk on blackboard, the shiver of wooden popsicle sticks on my teeth, the anxiety of a blaring tin whistle.

“I’m grateful for you.” The words leave my lips and it feels like the electricity these wires were waiting for. The words shoot off, charged and leaving streaks of blue light.

“I could never sleep in the same bed as someone else before I met you. I really liked how quiet and steady your breathing was and if you snored I could just say your name and you’d roll over. I never enjoyed sex with anyone as much as you…. it wasn’t as sweaty and like, I didn’t really feel cared for…” - whatever that means.

Then it’s all tumbling out, “…that time you booked me a doctors appointment because I hadn’t done anything about my cough…you’d always make sure to find ripe nectarines at the markets…I loved your face as you read your lame fantasy books, like terror and humour and sadness, all so obvious…the swoop of your cowlick…your laugh…the shape of your calves.”

My heart raced. I was silent. I felt a chill settling in, so much energy expended in bringing all this out and shouting it into those wires.

A road train screeching on wet bitumen, an aeroplane engine whining up to full power, a torrent of water down the drain - and me drowning in it all.

There was no answer.

I opened my eyes. I stood underneath a bare oak tree. The drizzle and the cold plastered my clothes to my skin and I was shaking.

I looked up and found that single wire hiding between the branches. I knew instantly that it couldn’t carry my message, it couldn’t convey my longing for my skin to be touching his skin, or to push my hands through his salty beach hair.

A murmur of a sleeping child, the buzz of bees at the end of the garden, the in and out breath of a calm ocean. A zephyr.

Was that even a word?

I didn’t speak the language but perhaps I didn’t need to. My body knew it. I ran the two hundred metres home. I barrelled through the front door I’d forgotten to lock and picked up my mobile phone.

As it rang I thought of those mighty cables running under the sea bed, bridging the distance between countries, cables wide enough to transmit my every intention. But that’s just words. My breath slipped out, that’s painful to realise -

The ringing cut to the silence of an answer and I knew I’d been looking for something to bind from here to there, me to him, and stitch up any wound I’d created. No amount of standing in the desert listening to some Aboriginal superstition was it even an indigenous thing? …it wasn’t going to tell me how to do that.

I heard the pause on the other end and I threw myself in, “Hi, mate. I’m sorry I never asked you to come.”

The lingering notes of your favourite song, the laugh of someone you love, the cry of your name at the Arrivals gate of the airport.

about Jacob (he/him/his)

Jacob is an Australian transplant to Shopshire, UK. He's a commissioned screenwriter and MSA graduate of the Australian Film, Television & Radio School. If he's not busy on one of a number of historical drama or horror scripts, then might be found programming Queer cinema or pretending that clearing his streaming watchlists is justifiable "work".

His writing deals in trauma, grace and places of belonging, namely home.

Twitter: @JHBScreenwriter

Instagram: @aknighterrant

about the illustrator:

Benedict Leader (he/him/his)

Benedict practices illustration and book-binding in London, UK. He studied history at University College London and likes to incorporate ideas of the archive, memory and queer theory into his drawing.

Working at a botanical gardens, the natural world is a key influence in his work, too. Instagram: @kiwi_marmelade